When we think of the history of audio, it appears to be a series of continuous improvements, from primitive origins to our current state of the digital art. The earliest recorded music, Edison wax cylinders from the 1890’s, were indeed crude, just as iPods and iPads are extremely sophisticated. No one wants to use a television or computer from 5 or even 10 years ago. Yet somewhere in the progression of music reproduction technology in the 20th Century, the quality of sound did not improve and even declined. This deterioration is so counterintuitive it requires more than just an explanation. We need to look at the history of audio reproduction to understand what happened.

ORIGINS

It’s impossible to know when man started to make music. Perhaps it was even before man was human, or Homo Sapiens. It is safe to assume it was a very long time ago. Some conjecture that music is a defining quality of what makes humans human. But one thing is certain- for at least tens of thousands of years, when music was made, you had to be present to hear it. A much larger number of people played an instrument, or sang, because that was simply the only way to have music. The advent of musical reproduction should be seen as a watershed in human civilization, and a high point in the history of technology. And the history of musical reproduction turns out to reveal a hidden secret about technology in general, one that belies our implicit faith that technology is like evolution in the natural world.

Virtually everyone today is immersed in music. It may come from your iPhone or iPod, but you certainly endure it in nearly every shop, store or public venue. Music is everywhere, and for most, costs nothing. And what costs nothing, is often considered without value.

When music was first reproduced, the situation was entirely different. The fact that you could hear music without being present for its live performance was nothing less than magical. Before electronic microphones, musicians and singers had to perform into long conical horns, which fed a mechanical transducer that cut the signal onto a cylinder and later, a record. It was the actual force of the voice or instrument which physically moved the transducer which created the signal on the recording medium.

Electronic microphones arrived in the 1920’s, and changed everything. A voice or instrument could now be electronically amplified, and anything could be recorded, such as a symphony orchestra.

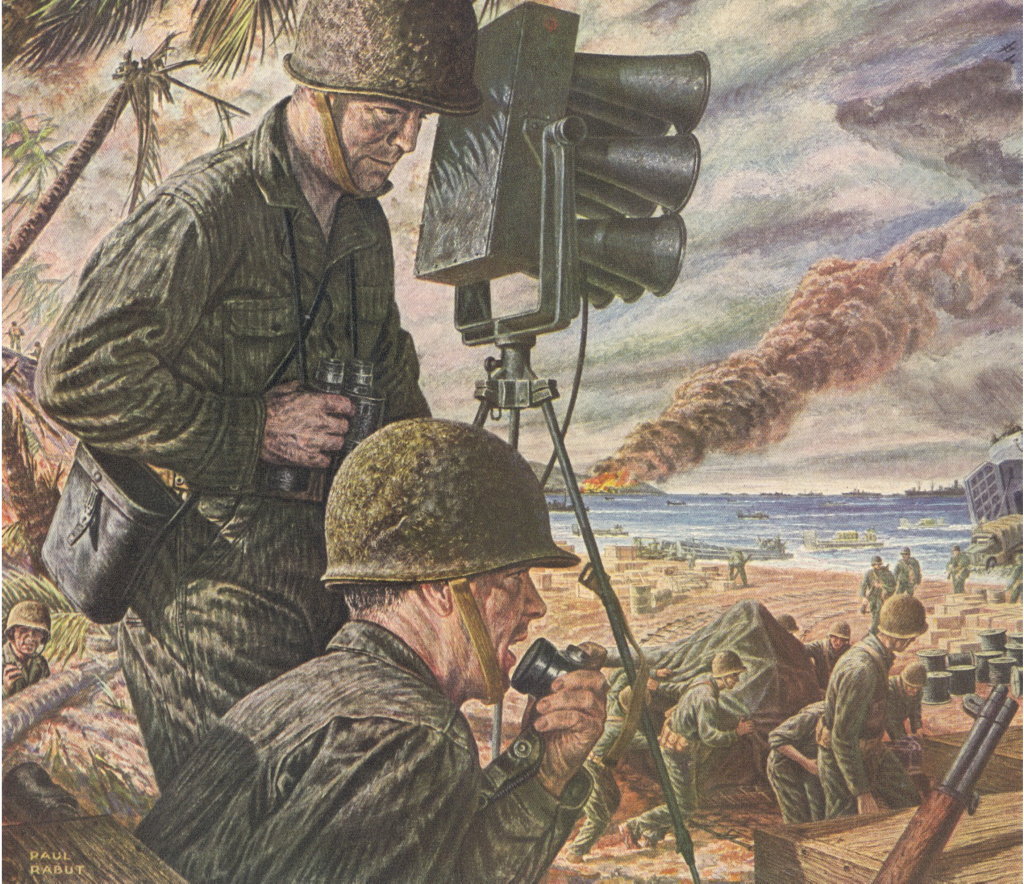

The 1920’s were a period of unprecedented prosperity in the United States and Europe. An enormous amount of money and effort was expended in the US, Germany, and elsewhere to develop the technology for advanced sound reproduction- meaning the telephone, microphones, recording technology for records, radio, and of course, talking motion pictures. Movies were an integral part of life like television or the internet are today. There were newsreel theaters in major cities that functioned like television, and ran 24/7. The invention of the “talkies” or movies with sound was an enormous event. It immediately and permanently changed film and all media.

Two huge corporations would literally dominate American and even worldwide communications technology for most of the 20th Century: RCA and Western Electric. These companies were responsible for nearly everything we take for granted today- the telephone system, RCA (at the time Victrola) invented record technology, created television, the VCR, and both were responsible for virtually all of the seminal development of sound for motion pictures, which is the reason for this essay.

It’s useful to remember that in the 1920’s and early 30’s, when the most significant theoretical and engineering work was being done by W.E (Bell Labs) and RCA, there were no computers, no space program or nuclear energy or weapons, and WW2 was not even on the horizon. The best minds in the world were working on the problem of how to reproduce sound effectively and realistically, and one of the most difficult challenges was how to make sound work in movies. It obviously requires a lot of sound, and that was a problem.

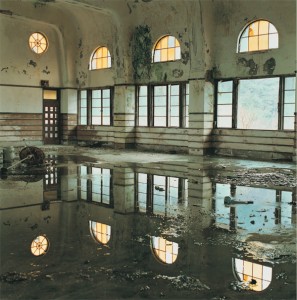

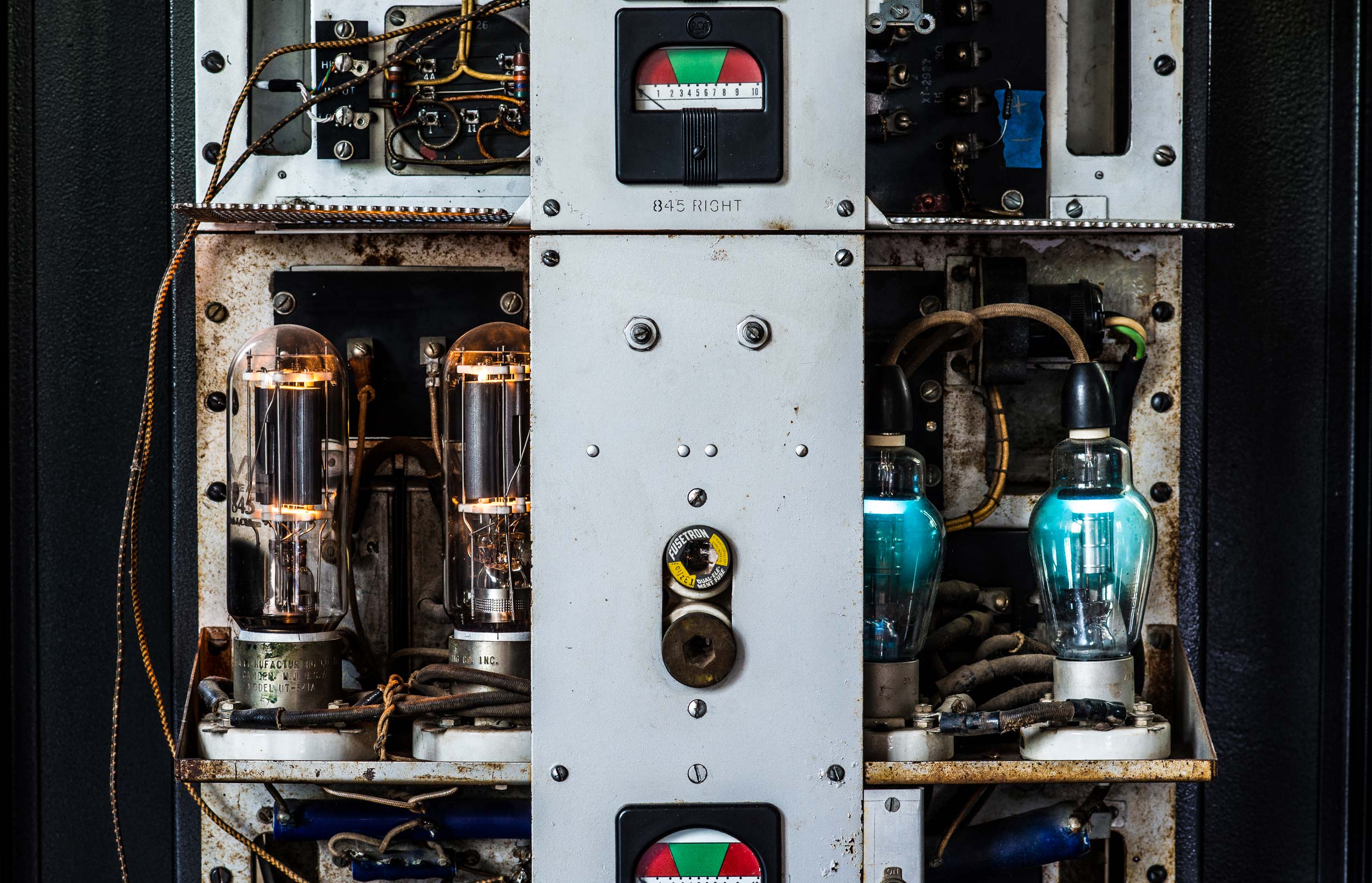

Theaters were not the small multiplexes of today. They were usually enormous caverns often holding thousands of people. Theaters have lots of upholstered seats, heavy drapery, and the audience themselves absorb a lot of sound, making sound reproduction even more difficult. The demand for loudness was great, but the first generations of amplifiers, which used the simplest type of vacuum tube, called a triode, produced very little power, usually not more than 10 watts per amplifier. Even if you had multiple amplifiers, which were very large and expensive, the total power available to produce credible sound for a big audience was tiny, much less than any mass produced audio amplifier made today. How did they turn so little power into so much sound?

THE GOLDEN AGE

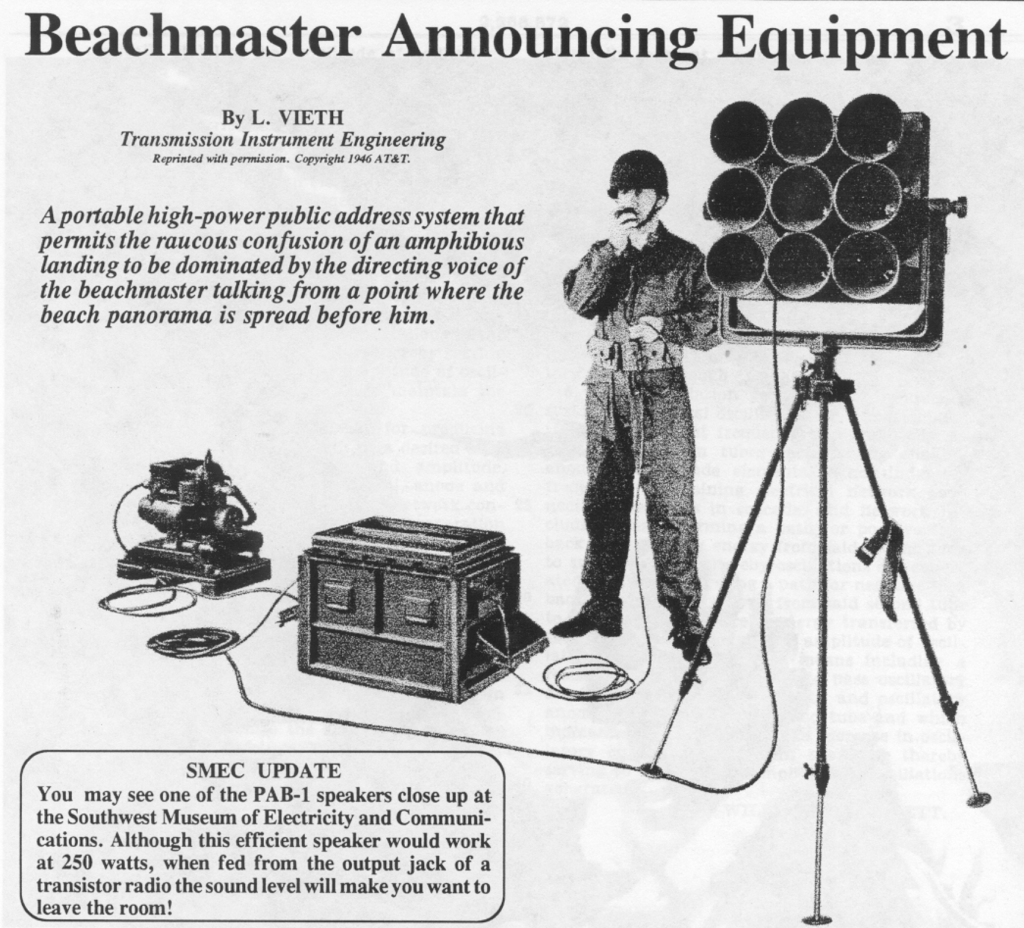

The answer was horns. Not that horns were a new thing- since antiquity, horns were used to make music, to communicate over long distances (those long Swiss ones) and to destroy buildings (Jericho, the Old Testament.) Engineers at Bell Labs and Western Electric (Wente, Thuras, Fletcher) and RCA (Volkman, Masa, Olson) took horns to a new level. These new horn loaded loudspeakers, which were very large and located behind the screen (see the essay “Why Horns”) were so efficient that they could convert the tiny electric power of the triode vacuum tube amplifiers into plausible, realistic sound levels in even the largest theaters. Without the aid of computers, in an almost miraculous way, these engineers mastered problems in acoustics and psycho-acoustics which are difficult even today, with our battery of modern technology.

Even die hard audiophiles, including the people who write audio magazines in the US like Stereophile or The Absolute Sound have never heard (or have any idea) about this combination of low powered triode amplifiers and large, horn loaded speakers. It has become the secret domain of a tiny group of advanced audiophile collectors, mainly in Japan and Asia, who have bought most of the vintage equipment that remained in North American theaters after World War II. There are only a few hundred such systems in use in the world today. What happened to make something that sounded so good simply disappear?

THE SLOW DECLINE

Most of us measure technology by its benefits. Computers get smaller, thinner, lighter, cheaper and more powerful every year. Those computers now allow us to store inconceivable amounts of information for a tiny sum, including music. Convenience and economy would seem to be the end of the story for most people, who now view music as wallpaper, background, or just distraction. Music is no longer an event, an end in itself, or most importantly, a source of deep pleasure and spiritual renewal. It can’t be, because it has been hollowed out at the core. This destruction has happened in several distinct ways. Let’s start by looking at why those great cinema loudspeaker systems from the 1930’s disappeared.

CHEAPER, NOT BETTER

Before WWII, all cinema loudspeakers, which were mounted in horns, used a speaker “driver” which is essentially an electrical motor. An electrical signal (from the movie soundtrack) is turned into mechanical movement (of the drivers diaphragm) and this produces the sound, which is greatly increased by the horn. In the early days of cinema sound, permanent magnets powerful enough to make the driver work properly did not exist- the metallurgy after the war made them possible. The early drivers all used “field coil” technology, which was electromagnetic. These field coils were very expensive to make, and because the permanent magnets were so much cheaper, the early technology was discarded as soon as possible (after WWII.)

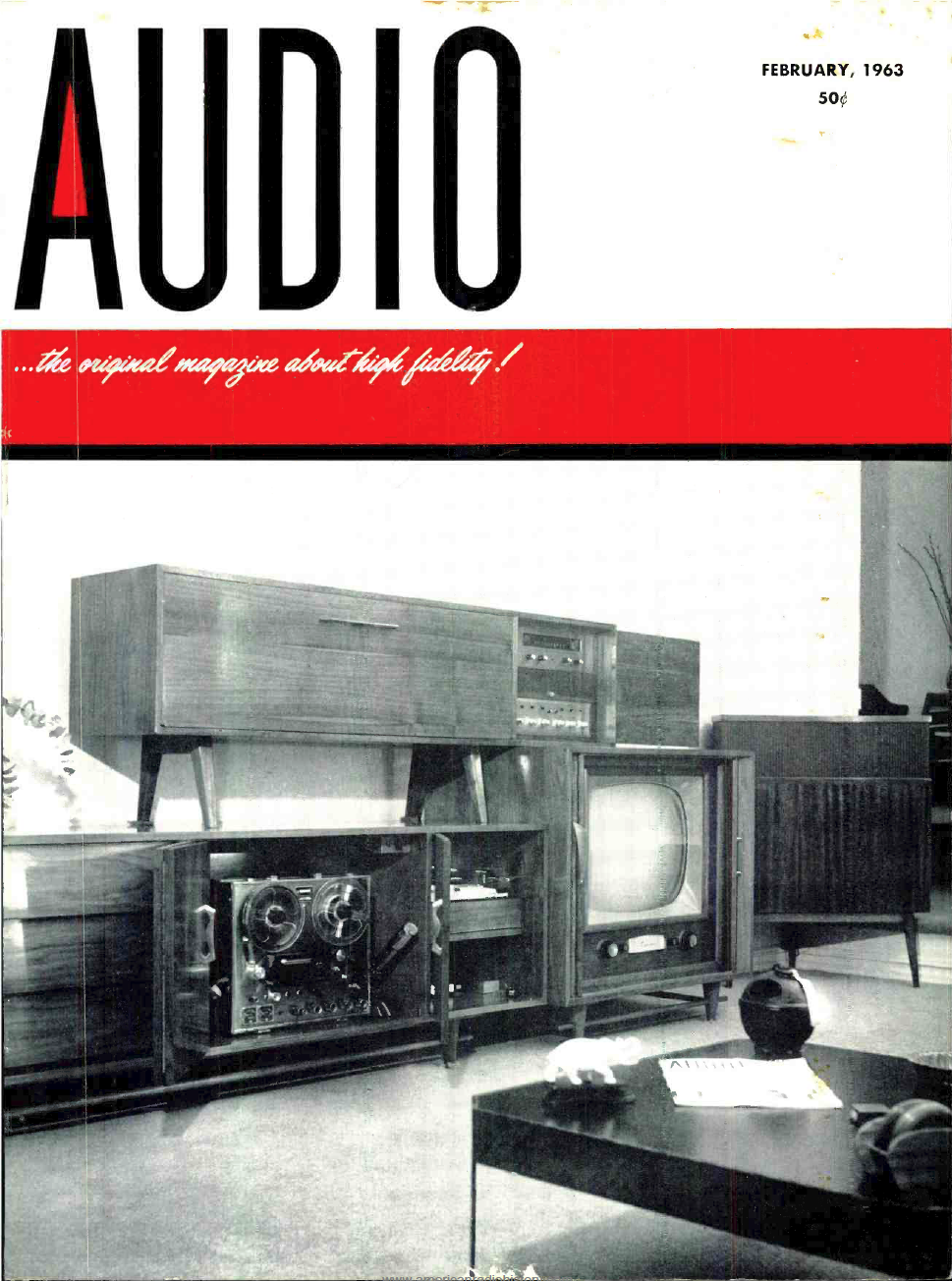

Equally important, the triode amplifiers of the first generation of sound systems, being low powered, were quickly replaced by pentode and tetrode type vacuum tubes, which were acknowledged to sound inferior, but again were cheaper and produced far more power.With the economic boom in the US after WWII, and the introduction of the LP record, and a lot of men trained in electronics by the war effort, home audio enjoyed enormous popularity. Because sound was monophonic, only one speaker was necessary, and they were always large, and virtually all of them used at least one horn, a vestige of the work done on cinema sound decades before. These speakers were all high efficiency, because amplifiers for the home rarely boasted more than 20 watts of power.

Power in audio is of the utmost importance, because it dictates how efficient, and thus how big, your speaker must be. Low power means a big speaker, which is a more expensive speaker, but a better sounding speaker. With more powerful tube types, speakers could be reduced in size and cost. The tipping point came with the introduction of solid state amplifiers; transistors replaced tubes entirely. If a watt of tube amplifier power cost $10, a watt of solid state cost 25 cents. Suddenly, loudspeakers did not have to be large at all- you can engineer a tiny speaker to produce the same sound pressure level as a big speaker, if you hit it with 100 times the power. Since power was cheap, and efficient speakers were expensive, the combination of cheap power and cheap, small speakers drove the audio industry into a downward spiral of sound quality from which it has never recovered. Solid state amplifiers continue to increase in power and decrease in cost. In turn, speaker manufacturers reduce the size of their product to conform with the perceived desire of the consumer for a speaker as small as possible. The actual result is ever worsening sound, with most people today having no real stereo system at all, and a tiny, insular “high end” audio industry which is dying.

DIGITAL VS. ANALOG

Few things are more deceptively simple than the vinyl record. It has been around for over a century, so how could anything that old work so well? Just as the original patent for the moving coil loudspeaker of Rice and Kellogg (1924) nailed the design of every cone speaker ever made since, the record was a stunning technical achievement which is still unsurpassed for audio quality (excepting master tape, from which records are cut.)

It sounds vaguely Luddite, but the earliest vinyl format, the 78rpm record, is still technically by far the best. Almost all surviving 78’s have a lot of groove damage (played by countless steel or cactus needles) and surface noise, but if you listen past that, something amazing happens. There is a lifelike quality, which is no mystery- 78’s spin much faster that 33rpm records, and with faster playback speed, more sonic information is conveyed. But 78’s only contain a few minutes of music per side, and were quickly replaced by the LP or Long Playing Microgroove record, the monophonic precursor to stereo sound.

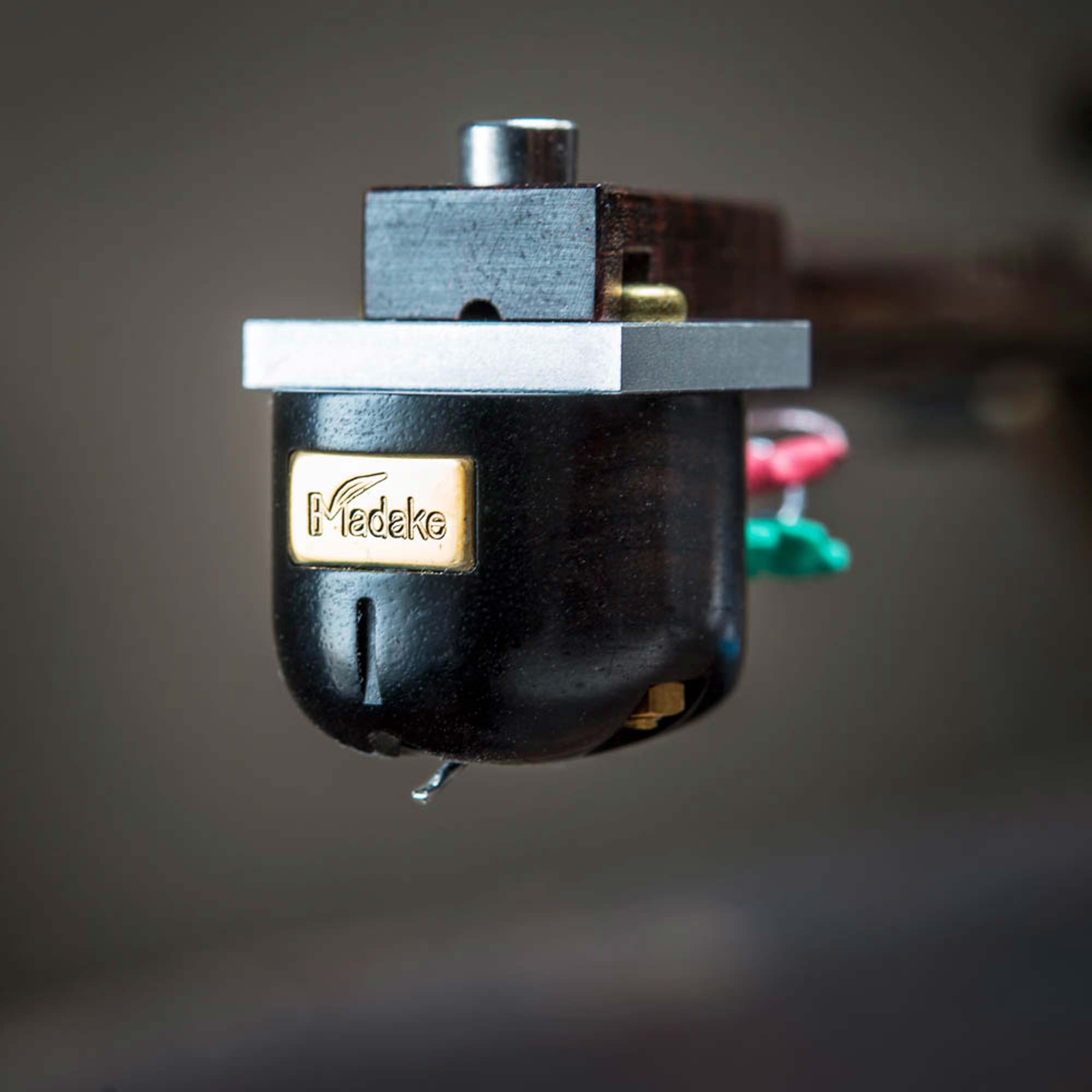

Records, whether 33rpm, 45 or 78, contain musical information in the “analog” format, which means the signal is continuous. A little tiny diamond point, sitting on the end of a tiny stick of aluminum, sapphire, boron or other material (the “cantilever”) literally traces the musical signal in a record’s grooves which look like squiggles and bumps. That tracing movement is turned into incredibly tiny electrical signals inside the cartridge, by the movement of magnets or coils at the other end of the cantilever. It’s like an electrical motor, but in reverse. This is all taking place at a physical scale so small it belongs in nanotechnology, with electrical signals that can be so infinitesimal that they are nearly on the molecular scale (pico volts.) The fact that this works at all is remarkable, but that it works better than anything we have today, in terms of sound quality, is mind boggling.

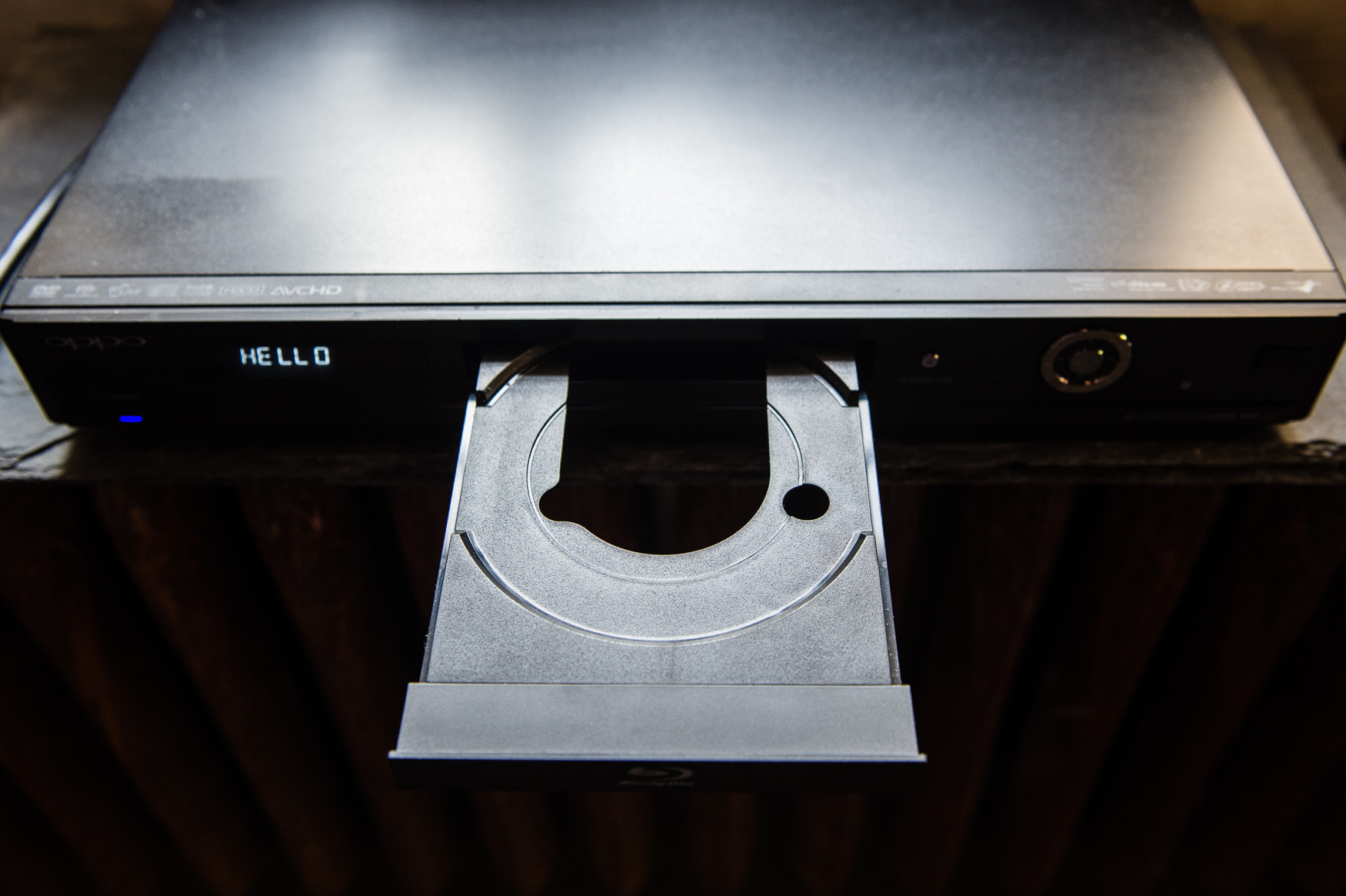

The problem with records is that they were expensive to make, as were record players and everything associated with analog reproduction. The compact disc was supposed to take care of that- no more scratched or dirty records, broken needles, and of course, the CD was far cheaper to make, about 20% of the cost of making an LP. The original marketing slogan for the CD was “Perfect Sound Forever” TM even though it was understood by Philips and Sony, the creators of the CD, that the sampling rate was far too low, with the final irony being that the material from which CD’s were made is now decomposing quickly, rendering many, if not all CD’s worthless in the future. The unintentional byproduct of making music digital, for the music industry, was its own destruction. The major labels used the introduction of the new format and technology to both raise the price of music for consumers (CD’s were more expensive to buy than LP’s, even if much cheaper to manufacture) and force people to abandon their analog music collection to conform with the new market reality. What they never anticipated was a Pandora’s box- with music now a stream of bits, it could be easily and endlessly copied, destroying the market for the physical purchase of music.

It has been 30 years since the CD format was introduced, and by now, even in the high end audio industry, no one is saying that digital is better than vinyl. If you open an audio magazine, it’s common to see ads for extremely expensive digital players which suggest that their product is “as close to analog” as possible. It’s also useful to note that although there are many technical theories as to why vinyl and analog are better than any digital medium, there is no proof as to why this is so. Human hearing is so complex and so accurate that science has not been able to fully understand why we can hear what we hear.

With digital file sharing, the MP3 format, Apple and iTunes, an already poor situation was made much worse. To enable easy and fast transmission of music files, not to mention ease of storage, compression was employed resulting in the (permanent) removal of as much as 80% of the original information. If we were to look at an image which had that much information removed, our impression would be negative. But the brain is very adept at filling in missing sonic information, based on a set of presumptions about what the unaltered musical signal should be. Thus even though low bass may not be present in an MP3, or on our headphones, our brains make believe that it exists. This wondrous ability comes at great cost, however, which is known technically as “listener fatigue.” Because hearing is such an unconscious activity, we are unaware of the brain’s work in restoring damaged or altered sounds. And since virtually no one sits down to seriously listen to music anymore, instead using music as a soundtrack to other activities, listening fatigue isn’t much of a problem. It does help explain why most people don’t own real stereo systems today- with digital, it’s not much fun to really listen to music.

On the professional side of digital audio, an equally disturbing phenomenon occurred in the middle 1990’s. With analog, a vinyl record can only be cut so loud, because if cut too loud, the needle will literally jump out of the groove. The record will not be playable. The CD has no such physical constraints, but until 1994 with the introduction of digital limiters, digital music was still recorded with dynamic range, which is defined as the relationship between the quietest parts of a recording and the loudest parts. Because record producers wanted their acts to sound louder over the radio than the competition, with the new technology they could eliminate dynamic range and make their music “seem” louder- by destroying a vital aspect of what makes music music. By the 2000’s, this phenomenon was referred to as the “loudness wars” and defines most digital music production today.

CONCLUSION

Technology is now advancing at such a rate that the amount of literature generated by it doubles every few years. Increasing specialization in the sciences and engineering has become necessary because no person can master even a single discipline with the proliferation of knowledge and information in any field. If you wander around an A.E.S. convention (the Audio Engineering Society, the worldwide professional association for audio) you can see the problem. Everyone is focused on a solution to their particular area of audio, improving digital algorithms, or reducing jitter in clocks, but the big picture (how does it sound?) is lost.

Scientists, engineers, and industry professionals furthermore are ignorant of the history of their field, and harbor a prejudice that with time, knowledge is both increased and perfected. In other words, history is irrelevant. In audio this is clearly not true, but to even acknowledge the possibility that prior art was superior would be epistemologically destabilizing.

We assume that technology is a progressive force, continuously improving and making our lives better. Looking at the history of sound reproduction belies this belief. Yet there are glimmers of a countermovement. The sales of vinyl records are growing enormously every year. That has led an avant garde of enthusiasts to discover vintage audio equipment, and even more esoteric horns and triode tube electronics. These are the people who listen with their ears, not their minds.